28 Sep Chloé CHARMILLOT – Through a selection of large-format works and prints…, 2021

Chloé CHARMILLOT

Through a selection of large-format works and prints, Galerie de l’ARTsenal in Delémont covers 30 years in the career of the painter and engraver Philippe Grosclaude. From inner wounds to societal realities, the Genevan artist makes human beings the laboratory of his art.

In Delémont, the gallery space is punctuated with large-scale paintings on canvas. At the center of the venue, two imposing, almost totemic works are hanging back to back. The oldest piece of this group dates to 1990. Making their way around the show, visitors immediately pick up on the artist’s concerns. Born in 1947 in Geneva, Philippe Grosclaude draws inspiration from human failing. It is the famous wound, the one that questions existence, torments the mind and pulls it into its meanderings, the one that extends to the mischief and mayhem at work in society.

A graduate of the École des Beaux-Arts in Geneva, Grosclaude is a seasoned artist who has exhibited numerous times in Switzerland, notably at the Musée des beaux-arts in Le Locle in 2002, and in galleries throughout both French-speaking and German-speaking Switzerland, including the Galerie Courant d’art in Chevenez, and the Graf & Schelble Galerie. His work has been singled out four times for a Federal Fine Arts Grant and the Boris Oumansky Prize. Last year, the Fondation Atelier Philippe Grosclaude was born. Located in Carouge and devoted to cross-discipline collaborations, the foundation is part of an approach that is committed to fostering diversity in art and culture.

AN ACCEPTED TENSION

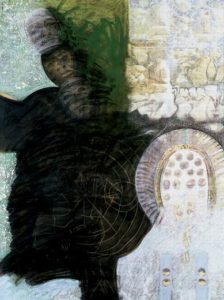

By uniting the amplitude of gesture and the ordering of abstract geometrical forms, Grosclaude’s paintings wield a tension that is fully embraced. While the elliptical or egg-shaped drawings lock up tight the interior of the composition, the beams he traces on the surface spill out of the work. He is one of those artists who like to defy the limits of the canvas. With their simultaneous contrast of closed elements and a free unhindered flight beyond the frame, the works give the impression they are radiating.

Sparking emotions, this resistance, this dual inner-outer movement displays his preference for large formats that make sweeping gesture possible. This range is accompanied by a finish that is fully mastered, meticulously carried out. The canvases aren’t the result of a quick and clean execution, a fever born of instinct. Rather they are rooted in a constant and deep inner need. Moreover, the draughtsman focuses on producing one work at a time and proceeds in his artmaking by series of layers. A way of not only entering the fullness of the act but also increasing a certain consistency in the work.

PASTEL AND VELLUM

Grosclaude is a physiognomist of the emotions. His characters, filled with an enigmatic, statuary presence, are not contorted. They vacillate between the absence of a face and masked portraiture. Stripped of details, the faces, which the artist works to erase, feed into an exaltation of sensations. It is in his prints, monotypes done in a smaller format, that the portraits of Black men assume another more direct importance.

To produce his compositions with their notes of the draughtsman’s art conjuring up graphic novels, charcoal, grease pencil and mostly pastel are used, while the engravings are done on vellum. The use of this paper, with its silky texture, and pastel indicates a penchant for sensitively working the pigment. He whose signature is inscribed in a pyramid wields the paint stick for its greasy quality. Pastel offers a smoother finish, accentuates depth, and fills his works with a soft tactile intensity. In the end, if Philippe Grosclaude brings us face to face with our humanity, in what is most intimate in it and its universality, his art seems to be above all a tool for experimenting in and experiencing his reality.

Le Quotidien Jurassien, no. 215, 18 September 2021